Duelling Epistemologies

How Artists Hack Laboratories and Alter the Futures of Science

Paper | Regine Rapp + Christian de Lutz

Rapp, R. and Lutz, C. (2024) ‘Duelling Epistemologies. How Artists Hack Laboratories and Alter the Futures of Science’, in J. Velasco and K. Weber (eds) Bio-Art: Varieties of the Living in Artworks from the Pre-modern to the Anthropocene. Bielefeld: transcript, 181 – 203.

On bio art and the living

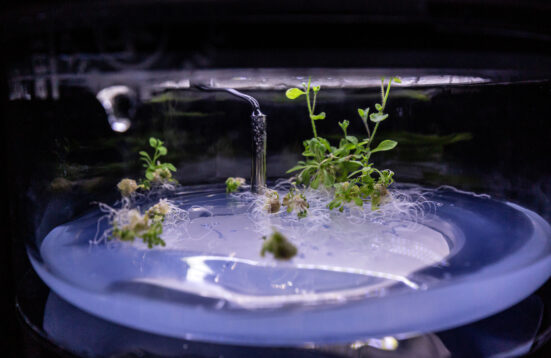

Bio Art challenges a number of western pre-conceptions about what art is and what art is supposed to do. By its nature ephemeral, and in a constant state of flux, the use of living materials runs contrary to centuries of art preservation and the ideal of art as eternal. But an art that goes hand in hand with science now ends two centuries in which the arts and science were seen as separate (and increasingly distant) disciplines. Moreover, Bio Art does not aim to ‘illustrate’ science (something which often confuses novice scientific collaborators) but to place the life sciences, and the organisms, cells and complex molecules studied, in a new focus. Many Bio Art works question whether Biology is, or can ever be, truly objective; and also seek to uncover the cultural and ideological baggage that the natural sciences carry with them, making clear that this baggage hinders both any true sense of objectivity – if this is even possible – and a deeper understanding of the living world. Bio Art has left the artist’s studio, as it ventures into new terrain, but it is also something more than “art made in the laboratory”. Along with new “post-humanities”, such as Science and Technology Studies (STS), the philosophy and history of science, and the new directions in Anthropology, Bio Art examines our civilisation’s cleft between scientists (and all humans) and the more than human world. But unlike those academic disciplines, Bio Art is about practice. After all the theory has been included, the artwork still has to function. It is a uniquely difficult practice that has to bridge both the ‘laws of nature’ and the debates of humankind. This essay was first published in Proceedings of Politics of the machines – Rogue Research 2021, in 2021.

Introduction

Donna Haraway’s concept of ‘Situated Knowledge’ can be understood as feminist critique of scientific ‘objectivity’, but there are more factors to critically challenge knowledge production – from the perspectives of race, gender, and class, as well as contemporary economic ideologies. Looking specifically at the interaction of Hybrid Art and the life sciences in the late 20th and early 21st century science we would like to formulate two lines of critical approach: 1) How can Hybrid Art, and specifically artistic research – in lab – criticize the effect that the market logic has on determining what is researched and what is not. Research funding can also be seen as a means of shaping and disciplining scientific research and knowledge, to ensure it follows the desires of the market. Can crossdisciplinary exchange between scientists and artists be a catalyst for liberation from market constraints and obligations? 2) What are the effects of ‘engineering’ as ideology on both science and Hybrid Art? Especially in the case of the life sciences, where money and attention are focussed on bioengineering, the ideal of efficiency creates an obstacle in the pursuit of knowledge. Efficiency, mandated by the market, plays a major role in bioengineering. But this is in contradiction to nature and life, where complexity and redundancy play a very important role in evolutionary success. Further, we live in an era where the ‘hype’ surrounding biotechnology creates a platonic mirage of the actual state of science. We propose, for example, that the CRISPR genetic engineering technique is not going to radically change nature as we know it and sustainable biomaterials are unlikely to replace plastics. Are both artists and scientists capable of sifting the hype from their research and practice, and if so, how?

Many hybrid artists do challenge the epistemology of natural sciences. They bring in questions of epistemology, ontology, ethics, and politics, yet remain true to principles of science. Instead of a ‘pure research’ which, despite its pretension for purity, in reality exists to provide marketable products, their hybrid artistic research seeks to (re)contextualize both knowledge and our species within a planetary ecology. In the long run (as opposed to market economy short-term profit goals) the approach of these artists asks questions about the survival of Homo sapiens. Also, their engagement with a diverse public, through their work but also new forms of media such as DIY science workshops (“do it yourself”), talks and inter-species performance broadens both knowledge and debate, as well as offering lay persons tools and knowledge for scientific literacy within a broader ethical, ontological, epistemological and political framework.

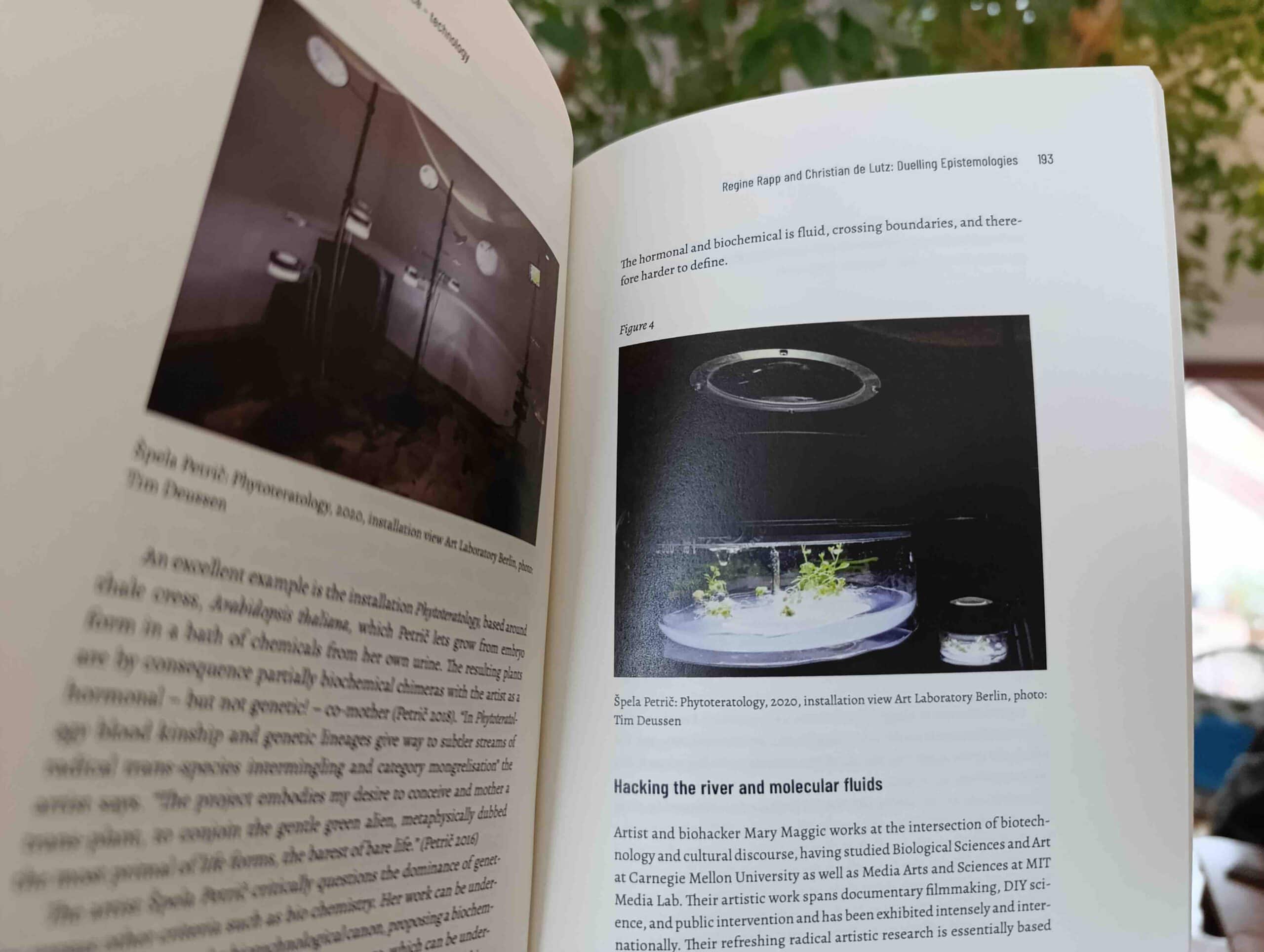

Reflecting situated knowledges

In her 1988 essay Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective Donna Haraway places natural science’s claim toward ‘objectivity’ under a wider scope of investigation. She claims that historically, science has been carried out in tandem with militarism, capitalism, colonialism, and male supremacy (Haraway 1988: 581). While the purpose of Haraway’s essay was to propose a ‘feminist science’ which would acknowledge and locate its bias, we think the power of the essay itself is in this initial questioning of the possibility of an objective science, and the locating of this so called ‘objectivity’ within the realm of power – gender power, racial power, and above all economic power. The point here is not to overturn ‘science’ as some sort of belief system, but indeed to create a stronger, more accurate concept of science, by examining and acknowledging the innate biases that are part of every action. In fact, it might be better to understand science from the get go as ‘scientific method’, or as a verb ‘to science’ – or ‘do science’, or carry out research by scientific method – rather than as a noun which, in the public imagination at least, occupies territory. That said, doing science still takes place within a world controlled and regulated by political and economic powers, whose desires support, hinder and shape most of the research actually taking place. Funding is probably the most important determinant of what is actually investigated – or on the contrary, what knowledge is left undiscovered. There is no simple formula here though, but rather a complex set of constantly re-aligning currents that determine what resources go where. In the last three decades since Haraway wrote her essay there has been an additional point of input into this complex system: calls for inter- and transdisciplinary practice, first within academia, and more recently from several generations of artists who have sought access to laboratories and research institutions with the goal of following their own hybrid practice. While the numbers of artists actually participating in research in scientific institutions and their influence upon these institutions is rather small – perhaps minuscule – we think it is interesting to ask here what role they might play, now or in the future, in challenging existing biases in the science, as well as opening up currently closed avenues of inquiry.

Excerpt, p. 181 – 184

Read the whole paper HERE.